C Pointer

指针是什么?

指针就是地址. 一个 8 bytes (在64位电脑下)的内存数据.

指针的意义是什么?

授予,存储一个值的这个变量本身以外的代码组分,对这个值的访问,修改权。 传指针,逻辑上就是一个授权,传了一个权利。 链表的节点。靠着这个权利,存储了对左右邻居的访问和修改权。 函数通过传指针,获取了外面一些变量的访问和修改权。 如果传值,只能获取访问权,不能获得修改权。

char * 指针

char *s = "abc";实际上是 const char *s, 因为 abc 数据是 readonly 的.

s 是字符串 abc 中 a 的地址, 可以用 s[1], s[2] 这种数组形式来访问字符 b 和字符 c.

相同的, char s[] 这里的 s 是数组名, 也是指针, 指向数组第一个元素的地址, 也可以用指针偏移来访问数据 *(s+1).

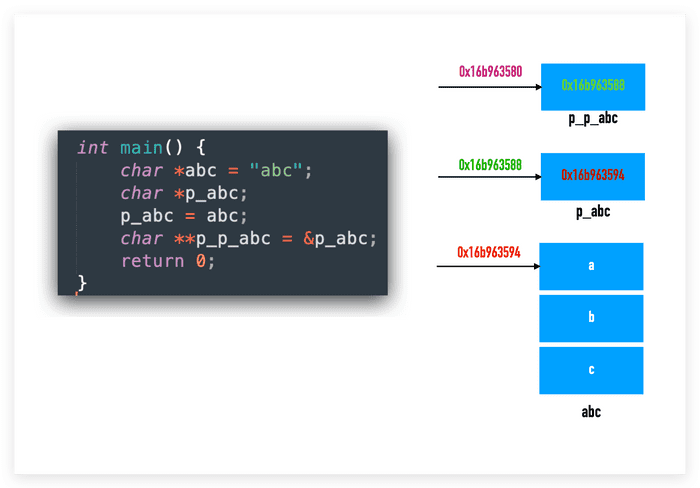

二级指针

它也是指针, 它的地址是另一个指针的地址:

int a = 1;

int *pa = &a;

int **ppa = &pa;

为什么这段代码是不对的?

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

char **s;

*s = "abc";

printf("%s\n", *s);

return 0;

}通过编译:

$ gcc -Wall -Wextra -Werror -ansi -pedantic -pedantic-errors -fsanitize=address,undefined a.c可以发现警告:

a.c:6:6: warning: variable 's' is uninitialized when used here [-Wuninitialized]

*s = "abc";

^

a.c:5:13: note: initialize the variable 's' to silence this warning

char **s;

^

= NULL

1 warnings generated.指针 s 没有初始化就被用了.

所以正确的写法应该是:

int main() {

char **s;

s = (char **)malloc(sizeof(char *));

*s = "abc";

printf("%s\n", *s);

free(s);

return 0;

}数组和函数

众所周知, int a = 1, 这里 a 代表着整形数字 1, char b = 'x', 这里 b 代表着字符类型 x, int* c = &a 中 c 代表着指针类型, 其值是 a 的地址, int d[] = {1,2,3} 中 d 是数组类型 int [N]. 而 d 在很多情况下可以变成(decay)指针, 比如 int* p = d. 但要明白 d 不是指针, 只是在这种情况下可以变成指针, 它和 &d 指向相同的地址, 也和 &d[0] 指向相同的地址, 而 &d 的类型是 int (*)[N]. 对于编译器来说, 数组就是数组, 很明显的一点就是通过 sizeof 来获取数组的大小, 在这里 sizeof(d) 是 12, 而 sizeof(p) 只是指针的大小 8.

对于函数也是一样的, 函数名就是函数所在代码的起始地址, 所以一个函数执行可以写为 func(2) 也可以写为 (*func)(2). 当然后者写起来非常 odd.

char **

char ** 这种写法指的是指向指针的指针, 当然也可以算做指向一个字符串数组的指针, 比如:

char *a[] = {"abc", "def"};

char **s = a;如何正确初始化一个具有两个字符串的 char ** ?

char **s = malloc(sizeof(char *) * 2);

*s = (char *)malloc(sizeof(char) *5);

s[1] = malloc(sizeof(char) *5);

strncpy(s[0], "a32q", 5);

strncpy(*(s+1), "dexg", 5);

printf("%c\n", *s[0]); // print a

printf("%c\n", **s); // print a

printf("%c\n", s[0][1]); // print 3

printf("%c\n", *(*s+1)); // print 3

printf("%c\n", *(*s+2)); // print 2

printf("%c\n", *s[1]); // print d

printf("%c\n", **(s+1)); // print d

printf("%c\n", *(*(s+1)+2)); // print x

printf("%c\n", **(s+1)+2); // print f

printf("%c\n", **(s+1)+9); // print m使用 char ** 解构 argv

for (char **p; *p != NULL; p++) {

printf("%s\n", *p);

}struct and double pointer

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

typedef struct tree {

char *name;

struct tree** children;

} tree;

int main() {

tree x = { .name = "namea" };

tree y = { .name = "nameb" };

tree* list[] = {&x, &y};

tree z = {

.name = "namec"

// .children = list // 1⃣️

};

z.children = malloc(sizeof(tree *) * 2);

*z.children = &x;

z.children[1] = &y;

tree *children1 = z.children[1];

children1->name = "namechildren1";

(*z.children)->name = "namex"; // or z.children[0]->name

// (*(z.children+1))->name = "namey";

printf("%s %s\n", x.name, y.name);

return 0;

}指针只能接内存地址。内存地址哪里来?一般两个来源,1,栈数组decay得到 2,malloc得到

在 1⃣️ 的地方, 是通过数组 decay 赋值内存地址, 如果不这样, 就需要下面的 malloc 方式进行内存初始化.

再回到开头的讨论指针的意义. 如果上述结构体中, 没有 ** 则外部传入的 children 则是内存的拷贝, 所以无法对外部的数据进行修改.

如果使用 * (一个星), 比如 node->next, 则只会有一个外部数据. 要想实现引用多个数据, 则可以用 ** 两个星的方式.

关于 realloc 的讨论

char* s = malloc(6);

strncpy(s, "abcd8", 5);

const char* s2 = "xyz";

memmove(s, s2, 4);

s = realloc(s, 3);

printf("s = %s, s2 = %s, s = %p \n", s, s2, s); // s = xyz, s2 = xyz, s = 0x13de06880

printf("strlen s = %ld\n", strlen(s)); // strlen s = 3

free(s);上面代码如果改成 memmove(s, s2, 3) 则 s 会是 xyzd8. 因为 strlen 只认 '\0'.

其实对于 string 的截断, 没必要用 relloc, 直接 s[3] = '\0'; 即可. 因为 relloc 会偷懒, 它发现给定的大小比原先的小, 于是就什么也不做.

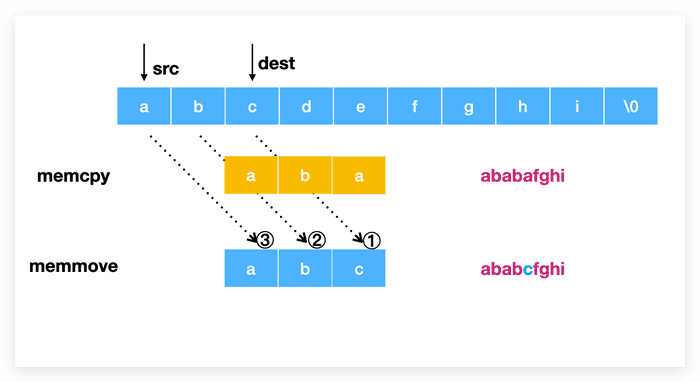

memcpy vs memmove

int main() {

char a[] = "abcdefghi";

// memcpy(a+2, a, 3); // ababafghi

// memmove(a+2, a, 3); // ababcfghi

// memcpy(a, a+2, 4); // cdefefghi

// memmove(a, a+2, 4); // cdefefghi

printf("%s\n", a);

return 0;

}

如果 src 的地址小于 dest, 那么 memcpy 函数可能会发生意外, 比如这个时候处理 overlap 数据部分, 复制到 c 的时候, c 其实已经被修改成 a 了, 所以最终结果还是 a.

memmove 进行了优化, 如果发现上述问题, 则从尾巴地方(也就是从 e)的位置开始复制, 避免了意外发生.

如果 src 的地址大于等于 dest, 则 memcpy 和 memmove 结果是一样的, 对 overlap 的数据进行覆盖, 也是不影响最终结果的.

pop

typedef struct foo {

char* name;

int count;

struct foo** others;

} foo;

foo* foo_pop(foo* f, int i) {

foo* r = f->others[i];

memmove(&f->others[i], &f->others[i+1], sizeof(foo*)*(f->count-i-1));

f->count--;

f->others = realloc(f->others, sizeof(foo*)*f->count);

return r;

}

int main(void) {

foo a = { .name = "fooa" };

foo b = { .name = "foob" };

foo c = { .name = "fooc" };

foo d = { .name = "food" };

foo x = { .name = "foox", .count = 4 };

x.others = malloc(sizeof(foo*) * 4);

x.others[0] = &a;

x.others[1] = &b;

x.others[2] = &c;

x.others[3] = &d;

foo* y = foo_pop(&x, 0);

printf("%s\n", y->name); // fooa

return 0;

}

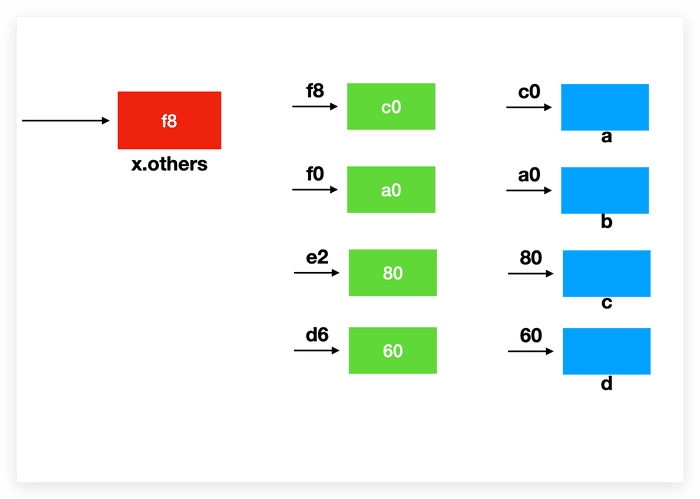

malloc(sizeof(foo*) * 4); 是开辟一块连续的内存数据, 每个数据块 8 个字节(因为存储的内容是指针嘛), 共 4 个.

然后对其赋值为 &a &b &c &d.

在 foo_pop 函数中, foo* r = f->others[0] 是将 r 设置为 f->others[0] 即 c0 地址(a所在), 而非所之前我所理解的第 0 号位置的指针. 如果想设置为第 0 号位置的指针应该写为 r = &f->others[0].

所以在 memmove 时候是需要将数组第 i 号的地址进行移动, 即 &f->others[i].

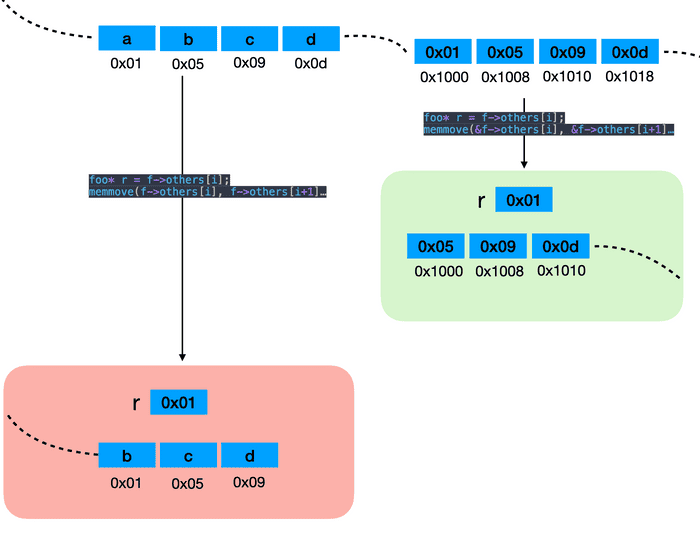

2024-02-11 update

上面的图表达的不是很清晰,又重新做了一张图:

首先要解释的是,a,b,c,d 四个变量在栈内存中,二级指针存储的是这四个变量的地址,如果是一级指针,那么无法直接设置其地址为四个变量的地址,一级指针只能重新复制内存。

foo_pop 函数的第一行将第 i 个地址赋值给 r 变量,因为后面会操作 others 这个二级指针,会让第 i 个地址丢失,如果不存给 r 变量,那么内存丢失后,就会造成内存泄漏。

第二行的 memmove 为什么是 &f->others[i] 而不是 f->others[i] 呢?上图中解释了,绿色区域是正确的用法,我们要操作的是 others 的数据,所以要传入 others 的地址,也就是 &f-others[i]。如果不带 & 那么memmove 操作的是 0x01 0x05 .. 这几个内存中的内容,所以会将原始数据给抹掉一个。